- Home

- Arun Kundnani

The Muslims Are Coming! Page 2

The Muslims Are Coming! Read online

Page 2

Whereas 9/11 was the defining event of the early war on terror, its later phase was shaped at least as much around acts of violence in Europe: the train station bombing in Madrid; the murder of filmmaker Theo van Gogh in Amsterdam in 2004; and the 7/7 attacks on the London transportation system in July 2005. The Obama administration’s domestic war on terror borrowed heavily from the counterradicalization practices Britain introduced after 7/7, which aimed to embed surveillance, engagement, and propaganda in Muslim communities. The linkages between the US and the UK approaches were multiple: ideas, analyses, and policies traveled back and forth between Washington and London. A flurry of public intellectuals, journalists, and think-tank activists from Britain—such as Peter Bergen, Timothy Garton Ash, Christopher Hitchens, Ed Husain, Bernard Lewis, Melanie Phillips, and Salman Rushdie—played prominent roles in forming American perceptions of Islam and extremism. Quintan Wiktorowicz, the architect of the Obama White House’s approach to counterradicalization, developed his ideas while working for the US embassy in Britain after 7/7. US terrorism experts gave evidence in British courts, and the State Department conducted its own outreach with Muslims in the UK. Meanwhile, a highly distorted picture of Britain’s Muslim “ghettos”—summed up by the specious term “Londonistan”—was circulated by journalists and bloggers in America as an apparent warning from across the Atlantic of what happens when Islam is accorded too much tolerance.17 There are significant demographic differences between the Muslim populations in the UK and in the US. In Britain, Muslims make up a larger percentage of the national population, are more often working class, and are less diverse in their ethnic origins. There are also important differences in the two countries’ political histories of multiculturalism and antiracism, attitudes toward religion and civil rights, and official cultures of counterterrorism. But especially since 2005, these differences have not been the barriers to the convergence of counterterrorism policies and the shared project of counterradicalization between the two countries that might be expected.

This book explores the domestic fronts of the war on terror in the US and the UK. It argues that radicalization became the lens through which Western societies viewed Muslim populations by the end of the first decade of the twenty-first century. Theories of radicalization that purport to describe why young Muslims become terrorists are central to counterterrorism policies on both sides of the Atlantic. But these models make an unfounded assumption that “Islamist” ideology is the root cause of terrorism. To do so enables a displacement of the war on terror’s political antagonisms onto the plane of Muslim culture. Muslims became what Samuel Huntington described as the “ideal enemy,” a group that is racially and culturally distinct and ideologically hostile.18 The political scientist Mahmood Mamdani had earlier identified such “culture talk” as the default explanation for violence when proper political analysis is neglected.19

Two main modes of thinking pervade the war on terror, one predominantly among conservatives, the other among liberals. The first mode locates the origins of terrorism in what is regarded as Islamic culture’s failure to adapt to modernity. The second identifies the roots of terrorism not in Islam itself but in a series of twentieth-century ideologues who distorted the religion to produce a totalitarian ideology—Islamism—on the models of communism and fascism. The problem with both of these approaches is that they eschew the role of social and political circumstances in shaping how people make sense of the world and then act upon it. Moreover, these modes of thinking are not free-floating. They are institutionalized in the war on terror’s practices, actively promoted by well-resourced groups, and ultimately reflect an imperialist political culture. Together they give rise to the belief that the root cause of terrorism is Islamic culture or Islamist ideology; they thus constitute an Islamophobic idea of a Muslim problem that is shared across the political spectrum. As a result, a key aspect of national security policy has been the desire to engineer a broad cultural shift among Western Muslims while ignoring the ways in which Western states themselves have radicalized—have become more willing to use violence in a wider range of contexts.

Islamophobia is sometimes seen as a virus of hatred recurring in Western culture since the Crusades. Others view it as a spontaneous reaction to terrorism that will pass away as the effects of 9/11 recede into history. Many believe it does not exist. My emphasis is on Islamophobia as a form of structural racism directed at Muslims and the ways in which it is sustained through a symbiotic relationship with the official thinking and practices of the war on terror. Its significance does not lie primarily in the individual prejudices it generates but in its wider political consequences—its enabling of systematic violations of the rights of Muslims and its demonization of actions taken to remedy those violations. The war on terror—with its vast death tolls in Afghanistan, Iraq, Pakistan, Somalia, Yemen, and elsewhere—could not be sustained without the racialized dehumanization of its Muslim victims. A social body dependent on imperialist violence to sustain its way of life must discover an ideology that can disavow that dependency if it is to maintain legitimacy. Various kinds of racism have performed that role in the modern era; Islamophobia is currently the preferred form. The usual objection to defining it in this way is that Muslims are not a race. But since all racisms are socially and politically constructed rather than reliant on the reality of any biological race, it is perfectly possible for cultural markers associated with Muslimness (forms of dress, rituals, languages, etc.) to be turned into racial signifiers.20 This racialization of Muslimness is analogous in important ways to anti-Semitism and inseparable from the longer history of racisms in the US and the UK. To recognize this obviously does not imply that critiques of Islamic belief are automatically to be condemned as racially motivated; it does mean opposing the social and political processes by which antipathy to Islam is acted out in violent attacks on the street or institutionalized in state structures such as profiling, violations of civil rights, and so on.21

The academic and official models of radicalization that have been central to the domestic war on terror have emerged within what the US and UK governments call a preventive approach to counterterrorism, in which an attempt is made to identify individuals who are not terrorists now but might be at some later date. But how do you identify tomorrow’s terrorists today? That was also the implied question posed by Steven Spielberg’s 2002 film, Minority Report, in which a specialist PreCrime Unit uses three psychics called PreCogs to predict who will be murderers in the future. The unit is then able to arrest precriminals before they have committed the crimes for which they are convicted. Likewise, a preventive approach to the war on terror would need its own PreCogs’ capability to identify the terrorists of the future. To meet this need, security officials turned to academic models that claim scientific knowledge of a process by which ordinary Muslims become terrorists; they then inferred the behavioral, cultural, and ideological signals that they think can reveal who is at risk of turning into a terrorist at some point in the future. In the FBI’s model, what they call “jihadist” ideology is taken to be the driver that turns young men and women into terrorists. They pass through four stages: preradicalization, identification, indoctrination, and action. In the second stage, growing a beard, starting to wear traditional Islamic clothing, and becoming alienated from one’s former life are listed as indicators; “increased activity in a pro-Muslim social group or political cause” is a sign of stage three, one level away from becoming an active terrorist.22 Only the last stage in this model involves criminal conduct but, as a New York Police Department (NYPD) paper on radicalization put it, the challenge is “how to identify, pre-empt and thus prevent homegrown terrorist attacks given the non-criminal element of its indicators.”23 What this implies is that terrorism can only be prevented by systematically monitoring Muslim religious and political life and trying to detect the radicalization indicators predicted by the model. Sharing an ideology with terrorists is thus considered a PreCrime, a stage in the radicalizat

ion process. “The threat isn’t really from al-Qaeda central,” explained former FBI assistant director John Miller, “as much as it’s from al-Qaeda-ism.”24 Deciding that al-Qaeda-ism—an ideological construct devised by the FBI—is a threat means that radicals who do not espouse violence but whose ideas can be superficially associated with al-Qaeda, such as Imam Luqman, come to be seen as would-be terrorists. In Minority Report, the PreCrime Unit is eventually shut down when the fallibility of the PreCogs is exposed. The FBI and other law enforcement agencies continue to rely upon radicalization models with no predictive power in order to shape policies of surveillance, infiltration, and entrapment.

The consequences of making the notion of radicalization central to the domestic war on terror are far-reaching. When the government widened the perceived threat of terrorism from individuals actively inciting, financing, or preparing terrorist attacks to those having an ideology, they brought constitutionally protected activities of large numbers of people under surveillance. Most discussion of state surveillance attends to wiretapping, collection of Internet communications data, closed-circuit television cameras, and other forms of electronic surveillance of our online and offline lives. Edward Snowden’s whistle-blowing has made clear the extent to which the US National Security Agency conducts warrantless surveillance of Internet and phone communication globally and domestically.25 But central to counterradicalization practice is another form of surveillance that is addressed less often: using personal relationships within targeted communities themselves for intelligence gathering. When community organizations and service providers such as teachers, doctors, and youth workers develop surveillance relationships with law enforcement agencies, when government community engagement exercises mask intelligence gathering, and when informants are recruited from communities, surveillance becomes intertwined with the fabric of human relationships and the threads of trust upon which they are built. The power and danger of these forms of surveillance derive from their entanglement in everyday human interactions at the community level rather than from the external monitoring capabilities of hidden technologies. Moreover, having established such structures of surveillance in relation to Islamist extremism, it becomes easy to widen them to other forms of radicalism—occasionally to cover the far Right, but more often to left-wing protesters and dissidents. Following from the widening of surveillance is the criminalization of ideological activities previously understood to be constitutionally protected. This can happen through the entrapment of individuals by law enforcement agencies or through measures criminalizing the material support of terrorism, the definition of which has been widened to include a broad range of ideological activities. Then, because ideologies circulating among Muslim populations have been identified as precursors to terrorism, the perception grows that Muslims have a special problem with radicalization. In this context, leaders of targeted Muslim communities have become intimidated by the general mood and aligned themselves with the government, offering themselves as allies willing to oppose and expose dissent within the community. Everyone who rejects the game of fake patriotism falls under suspicion, as opposition to extremism becomes the only legitimate discourse. Finally, the spectacle of the Muslim extremist renders invisible the violence of the US empire. Opposition to such violence from within the imperium has fallen silent, as the universal duty of countering extremism precludes any wider discussion of foreign policy.26

The planting of informants and agents provocateurs among networks of political radicals is a practice dating back at least 125 years, to the Russian tsar’s secret police, the Okhrana, and the early special branch at Scotland Yard. Lightly regulated intelligence services have long used techniques of provocation to disrupt political opposition, spread misinformation, and engineer violent crimes that would otherwise not have happened, thereby securing the conviction of dissidents. This was the countersubversion model the FBI’s COINTELPRO initiative drew on in its sustained and coordinated campaign to thwart constitutionally protected activism and counteract political dissent during the 1960s. Targets included the civil rights, black liberation, Puerto Rican independence, antiwar, and student movements. In an attempt to neutralize Martin Luther King Jr., who, the FBI worried, might abandon his “obedience to white liberal doctrines,” he was placed under intense surveillance, and attempts were made to destroy his marriage and induce his suicide. The Black Panther Party was disrupted in various cities by using fake letters and informants to stir up violence between rival factions and gangs.27 The congressional hearings initiated by Senator Frank Church in 1975 to examine the intelligence agencies concluded that the FBI’s activities

would be intolerable in a democratic society even if all of the targets had been involved in violent activity, but COINTELPRO went far beyond that. The unexpressed major premise of the program was that a law enforcement agency has the duty to do whatever is necessary to combat perceived threats to the existing social and political order.28

Those at the agency behind the initiative were never brought to justice for their activities, and similar techniques continued to be used in the 1980s against, for example, the American Indian Movement and the Committee in Solidarity with the People of El Salvador.29

In recent years, the US domestic national security apparatus has effectively revived the countersubversion practices of COINTELPRO. Campaign groups such as the Bill of Rights Defense Committee have dubbed “COINTELPRO 2.0” tactics that amount to a twenty-first-century countersubversion strategy: the extensive surveillance of Muslim-American populations; the deployment of informants; the use of agents provocateurs; the widening use of material support legislation to criminalize charitable or expressive activities; and the use of community engagement to gather intelligence and effect ideological self-policing of communities. Significantly, such practices have been encouraged, organized, and legitimized by the radicalization models that law enforcement agencies adopted in the first decade of the twenty-first century. Yet radicalization—in the true sense of the word—is the solution, not the problem. Al-Qaeda’s violent vanguardism thrives in contexts where politics has been brutally suppressed or blandly gentrified. Opening up genuinely radical political alternatives and reviving the political freedoms that have been lost in recent years is the best approach to reducing so-called jihadist terrorism.

In 1966, after the phantasmagoric anticommunism of the early cold war had been discredited and before its revival by Reagan, Hollywood released a characteristically liberal take on it. The Russians Are Coming! The Russians Are Coming! is in many ways a film that reflects our own moment in the war on terror. When a Soviet submarine accidentally runs aground near a small island off the coast of Massachusetts, a section of the crew goes ashore, leading the conservative townsfolk to think a Russian invasion has commenced. A ragtag citizens’ army is formed to hunt down the Russians. Only Walt Whittaker, a liberal writer visiting from New York, grasps the more mundane reality of the situation. As the sailors and the townsfolk confront each other, the hysteria is eventually broken when a young boy who has climbed up a church steeple to watch the showdown loses his grip and hangs precariously. Russians and Americans unite in forming a human pyramid to rescue the boy, and international harmony ensues. Film historian Tony Shaw notes that The Russians Are Coming! “depicted America not as a united, peace-loving nation, but divided between paranoid warmongers … and level-headed liberals willing to talk with the Russians, like Walt Whittaker.”30 The film positions itself on this liberal center ground, directing its humor at the excesses of early cold war paranoia while presenting the Russians not as dangerous communist ideologues but as human beings who—displaying a mixture of incompetence, heroism, and romance—behave just like Americans. This portrayal is an improvement on the “machine-like automatons bent on the enslavement of the Free World” who peopled the cold war films of the 1950s.31 However, the price the Russians pay for this advance is their depoliticization. “They do not make any explicitly political statements or hold any politic

al conversations among themselves. Neither they nor the islanders make any reference to the long-standing ideological differences between East and West.”32 The film’s implicit message is that conservatives are wrong to fear Russians en masse; instead, Russians should be admitted to the circle of humanity, so long as they leave behind their political ideology. This liberal version of the cold war thinks of ideology as what the other side has; America itself is essentially neutral.

Similarly, today liberal America finds it easy to condemn the early war on terror of the Bush years as a moment when hysteria took over, leading to blanket fears of Muslims and misguided warmongering. But now, liberals say, we have moved beyond that, and we understand that Muslims in America are just like the rest of us. However, just as in The Russians Are Coming!, the liberal caveat is that Muslims are acceptable when depoliticized: they should be silent about politics, particularly US foreign policy and the domestic national security system, and not embrace an alien ideology that removes them from the liberal norm. Two of the aims of this book are to ask what reasons there are for thinking Islamic ideology is the root cause of terrorism, and why the acceptance of Muslims as fellow citizens should be conditioned on their distancing themselves from any particular set of ideological beliefs.

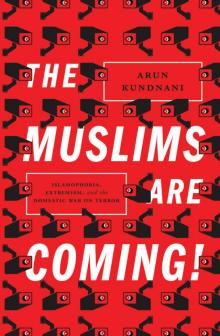

The Muslims Are Coming!

The Muslims Are Coming!